Chapter 3: Probability and Information Theory

Overview

- Two different types of probability: frequentist and bayesian.

- Bayesians approach treates probabilities as degrees of belief.

- Frequentist probability refers to the rates at which events occur, while Bayesian probability refers to more qualitative levels of certainty.

- Example of frequentist would be that flipping a fair coin comes up heads with probability $p = 0.5$, because if you flip the coin infinitely many times, half of the outcomes will be heads.

- Example of Bayesian probability is a doctor saying a patient has 40% chance of having the flu given some symptoms.

Marginal Probability

- when we want to know the probability distribution over a subset of variables.

- sum rule - $\forall x \in x, P(x=x)= \sum_y{P(x=x, y=y)}$

- For continuous variables, we integrate instead $p(x) = \int p(x,y)dy$

Conditional Probability

-

Probability of an event given that something else has happened.

- The chain rule of probability is super important . It basically lets us exprss a joint distribution as a conditional distribution.

- In 2 variables, we have $p(a, b) = p(a \mid b)p(b)$. In 3 variables, we have $p(a, b, c) = p(a, b \mid c)p(c) = p(a \mid b, c) p(b \mid c)p(c)$.

- In $n$ variables, we just keep applying this over and over: $p(x^1 … x^n) = p(x^1)\prod_{i=2}^{n} p(x^i \mid x^1 … x^{i-1})$.

- Note that we can still use the chain rule if we want to express a conditional joint distribution, for example if we have a joint distribution of our dataset $(x,y)$ conditioned on a parameter $\theta$ we have $p(x, y \mid \theta) = p(y \mid x, \theta) = p(x \vert \theta)$.

Independence and Conditional Independence

- Two random variable are independent if $\forall x \in x, y \in y, p(x=x, y=y) = p(x=x)p(y=y)$

- Two events are conditionally independent if $\forall x \in x , y \in y,z \in z, p(x=x, y=y \mid z=z) = p(x=x \mid z=z) p(y=y \mid z=z)$

Expectation and Variance

- Expected value of some function $f(x)$ where $x$ is a random variable is given by .

- Expectations are linear so

- Variance measures how much the values of a function differs from it’s expected value. If we have a low variance, this intuitively means that the values cluster around the mean with little deviation; if we have high variance, then the data are more spread apart. It is given by .

Covariance

- Measure of linear relation between 2 variables, and scales of the variables with respect to each other. High values of the covariance indicate that both random variables take on relatively high values at the same time, while a negative value means that one is has a larger value (i.e. right of it’s mean) while the other has a smaller value (i.e. left of it’s mean). Given by .

Covariance Matrices

- If we have a random vector $x$ (so each element $x_i \in x$ is a random variable drawn from some distribution, then we can construct a covariance matrix for x, denoted as $C$. Each element $C_{i,j}$ will denote the covariance between elements $x_i$ $x_j$, so also $C_{i,i} = Var(x_i, x_i)$.

Common Probability Distributions

- Bernoulli distribution - single binary random variable controlled by the probability $\phi$

- multinoulli distribution - a vector of where $p_i$ gives the probability of the $i$th state.

- $N(x; \mu, \sigma^2) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{2\pi\sigma^2}} exp(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}(x-\mu)^2)$ can also be expresed as a function of precision

- The Gaussian is a good choice for a prior on your model’s latent variables for 2 reasons: they encode the least amount of prior information into the model, and the central limit theorem tells us that we can model the sum of many independent random variables as roughly Gaussian (without knowing the distributions of those indepndent random variables.)

- Multivariate Guassian: is a generalitzation of the normal distribution to $R^n$. Instead of being parametrized by a single mean and variance it is now parametrized by a vector-valued mean and a covariance matrix.

Exponential and Laplace Distributions

- $p(x; \lambda) = \lambda \textbf{1}_{x\geq 0} exp(-\lambda x)$

- we can place a sharp peak any where via the Laplace distribution, which adds in a translation parameter $\mu$

Dirac Delta Function

- A way to specify a probability distribution where we put all of the probability mass on one point, and zero everywhere else, but the function is still a valid prbability because it integrates to one.

Mixture Modelling

- A way of combining probability distributions. In this case, $x$ can be thought of as a random variable that is sampled from a variable distribution. For example, you could sample $x$ from a unit Gaussian with $0$ mean with probability 0.5, and sample it from a unit Gaussian with 1 mean with probability $0.5$. Then $x$ would be a random variable that comes from a mixture of 2 Gaussians. In general, the probability of $x$ is given by $p(x) = \sum_i p(c = i)p(x \mid c = i)$.

- introduces the concept of a latent variable, which we cannot observe but may be related to $x$

- In the above case, $c$ is a latent variable, because we cannot directly observe it, but it affects $x$’s probabilities.

- In Gaussian mixture modelling, we have the probabilities $p(x \mid c)$ given by Gaussians. We also have prior probabilities on the Gaussians, which indicate how likely each individual Guassian is: $p(c = i)$. Given this information, we can also estimate the probability that given a certain $x$, which distribution $i$ did it come from: $p(c = i \mid x)$. This is the posterior probability of our Gaussians.

- Gaustrian mixture model is a universal approximator

Useful Properties of Common Functions

- logistic sigmoid saturates when it’s argument is very positive or very negative

- softplus function . This is a smoothened version of the rectified linear unit $f(x) = max(0,x)$ which is commonly used as a nonlinearity in deep nets.

Bayes Theorem

- We can interpret $y$ as being the class labels and $x$ as being our feature vectors. Bayes theorem tells us that we can obtain the posterior probabilities of $y$ given the likelihood $p(x \mid y)$, and the priors $p(y)$, and the evidence $p(x)$. Given these, we can estimate the most likely class that $x$ belongs to by computing $argmax_{y} p(y \mid x)$

Technical Details of Continuous Variables

- measure theory provides characterization of the sets of sets we can compute probabilities on.

- measure zero is a set of negligibly small size. A property that holds almost everywhere holds throughout all space except for a set of measure zero.

Information Theory

- self-information of an event $I(x) = - \log P(x)$

- Field that seeks to quantify how to encode information in signals optimally. We’d like likely events to take up a small amount of space (and gauranteeed events 0 space), and unlikely events to take up more space (since they are less likely to happen, they give more information about the state of the world.)

- Kullback-Leiber divergence

- Importantly, the expectation is taken using probabilities from $P$.

- The KL divergence is similar to the cross-entropy loss function. The only difference is that the cross-entropy doesn’t have the term on the left, so it is just $-E[\log Q(x)]$

- Intuitively, the KL divergence measures the “difference” between 2 probability distributions, $P$ and $Q$. The parameters that minimize the cros s entropy and KL divergence are equal, and you can think of minimizing the KL divergence in the context of machine learning, to mean that you want the distribution of your output probabilities to exactly match that of the distribution of your true class labels.

Structured Probabilistic Models

- Often, we are given a large joint distribution, and want to factor it into a composition of functions of relatively fewer variables.

- For example, if we have the joint $p(a, b, c, d)$ then we could write that out using the chain rule of conditional probability $p(a, b, c, d) = p(a \mid b, c, d)p(b \mid c,d)p(c \mid d)p(d)$. However, if we know certain things/make certain assumptions about these probabilities (such as a only depends on b and nothing else), then we can dramatically simplify the above expressions.

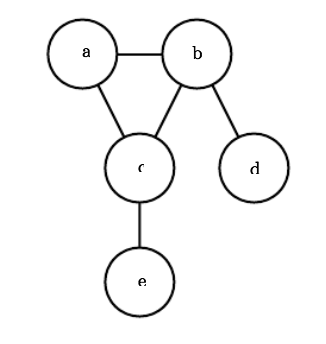

- These simplified conditional expressions can be modelled as a directed graph, where nodes with no incoming edges do not depend on any other variables, and nodes’ incoming edges denote the variables that they do depend on.

- Given that the directed models have direced edges, we can compute $p(x)$ by tracing back it’s connections with $p(x) = \prod_ip(x_i \mid P_{aG}(X_i))$

- The probability of random variables is proportional to the product of all these factors.

- The above directed graphical model indicates that $e$ is conditioned on $c$, $c$ is conditioned on $b$ and $a$, etc. Also, we can see that $p(d) = p(d \mid b) p(b)= p(d \mid b)p(b \mid a)p(a)$