Chapter 4: Numerical Computation

-

Computers have finite percision, so we must deal with rounding errors such as underflow and overflow.

- Softmax example of overflow and underflow: The softmax function is given by

- This could overflow if any $x_i$ is very large, or underflow if any $x_i$ is very small. Therefore, it is common to normalize the function by subtracting $max(x)$ from each element before running it through softmax; this way the largest argument will be $0$ and we are guaranteed that the denominator will not evaluate to $0$.

- If you do $\log softmax(x)$ also make sure that the input to log isn’t 0. If it is, adjust it to some extremely small value.

Poor Conditioning

- condition number is given by

- poorly conditioned functions change rapidly when their inputs are perubred slightly.

- A condition number gives an idea about the relative curvature of a function. For example, a condition number of $5$ means that the direction of most curvature of that function has $5$ times more curvature than the least-curvature direction.

Gradient Based Optimization

- Usually framed in terms of a minimization problem, i.e. find $x* = \arg \min_{x} f(x)$.

- Main idea of learning via gradient descent is to take a function $f(x)$, evaluate it’s gradient $f’(x)$, and take a step in the negative direction: $x_1 = x_0 - \epsilon f’(x)$, and then (for small enough $\epsilon$) we know that $f(x_1) < f(x_0)$.

-

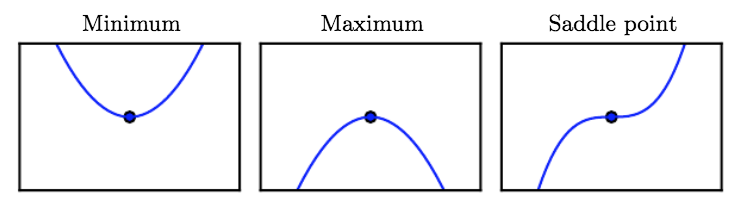

When $f’(x) = 0$, we’ve reached a critical point, which can either be a local minimum, maximum, or saddle point:

- for a function $y=f(x)$, it’s derivative is such that $f(x+\epsilon) \approx f(x) + \epsilon f’(x)$.

- when we deal with multiple inputs, we use the partial derivative - $\frac{\partial}{\partial x_i}f(\textbf{x})$

- We can generalize this to taking the gradient $\nabla$, which contains the partial derivative for each element of a vecotor - $\nabla_xf(x)$

- We’d like to ideally find a global minimum, but in the context of deep learning the functions have many local minima and saddle points, so we just seek to find a “low enough” value for $f$ that may not be minimal in any sense.

Derivation of Steepest Descent

- $u^T \nabla_xf(x)$ gives the derivative of $f(x)$ in the direction given by the unit vector $u$.

- We have to find the direction in which $f(x)$ decreases fastest. This is

- We set $\cos \theta = -1$, meaning that $u$ is pointing in the opposite direction of the gradient.

- This gives us our gradient descent, or “steepest descent” update rule: $x:= -\epsilon \nabla_x f(x)$.

Strategies for selecting the learning rate

- Common: set it to a small constant

- Line search: evaluate $f(x - \epsilon \nabla_x f(x))$ for several $\epsilon$ and choose the one that results in the smallest value of the objective.

Higher Order Methods

-

sometimes we need to find the partial derivates of a vector valued function, which gives us a Jacobian matrix. For a function $f: R^m \rightarrow R^n$ the Jacobian $\textbf{J}{n,m}$ is defined so $J{i,j} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}f(\textbf{x})_i$

- The second derivative of a function is a measure of the function’s curvature. In the vector setting, the second derivative is given by the Hessian Matrix, a matrix of second-order partial derivatives. Its elements are denoted by $H(f)(x){i,j} = \frac{d^2}{d{x_ix_ij}} f(x)$.

- Since the Hessian is real and symmetric, it can be decomposed into eigenvalues and an orthogonal basis of eigevencectors $d^THd$. When $d$ is an eigenvector of $H$, the second derivative in that direction is given by that eigenvalue, so the max eigenvalue gives the maximum second derivative while the min eigenvalue gives the min second derivative.

-

We can use the directional second order derivative to figure out how well a gradient descent step may perform.

-

If we create a second order taylor approximation, $f(x) \approx f(x^0) + (x-x^0)^T \textbf{g} + \frac{1}{2}(x-x^0)^T \textbf{H} (x-x^0)$

- If we use our gradient descent step, our new point is $x^0 - \epsilon\textbf{g}$.

- If we substitute this into our above approximization, we obtain $f(x^0) - \epsilon \textbf{g}^t\textbf{g} + \frac{1}{2}\epsilon^2\textbf{g}^T\textbf{H}\textbf{g}$.

- If we look at the last term (involving the Hessian), it tells us that when the directional second derivative of $H$ if large, then the gradient descent step may move uphill.

- On the other hand, when $g^THg$ is zero or negative, the approxmiation tells us that the $\epsilon$ we chose does indeed (approximately) decrease $f$.

- In order to find the optimal $\epsilon$, we can find the step size that decreases the Taylor series buy taking the derivative of the Taylor approximation and setting that equal to $0$. This gives us $\epsilon = \frac{g^Tg}{g^THg}$.

- In the worst case when $g$ is an eigenvector of $H$ with maximum eigenvalue, the step size is given by $\frac{1}{\lambda}$. This means that the larger our max eigenvalue gets, the smaller step size we can take, meaning that the eigenvalues of the Hessian approximate the scale of our learning rate.

- The second derivative can be used to determine whether a critical point is a local maximum, a local minimum, or a saddle point via the second-derivative test. When the second derivative is positive/negative at a critical point, we can say that x is a local mininum/maximum. When the second derivative is 0 the test is inconclusive.

-

We can generalize the second derivative test to multiple dimensions and make use of the HEssian. When the Hessian is positive definite (meaning it has all posittive eigenvalues), then the point is a local minima. This can be seen by noting that the directional second derivative is going to be positive in all directions because all the eigenvalues are positive.

- the condition number of the Hessian measures how the curvature differs along different directions - if the condition number is high, gradient decent performance may suffer, as steps may be made that oscillate along the high curvature sides.

- Basically the issue is that in multi-dimensional space, gradient descent alone cannot tell the differences in directional derivatives. And we may have cases where the derivatives in certain direction differ greatly from one another.

- This can be resolved by including Hessian information, using methods like Newton’s method

- Newton’s method critical point is given by $x* = x^0 - H(f)(x^0)^{-1} \nabla_x f(x^0)$ (basically the initial point minus the first derivative over the second).

- If $f$ is a positive definite quadratic, this is the global minumum, else it is applied iteratively.

-

We sometimes restrict ourselves to Lipschitz continuous functions, where $\forall x, \forall y, \vert f(x)- f(y) \vert \leq L \Vert{x-y}\Vert_2$

- Convex optimization can provide many more gaurentees, but only for functions where the Hessian is positive semidefinite everywhere.

Constrained Optimizattion

- Limit the minimum and maximum values of $x$ to have to be in some set, known as the feasible points.

- Common to impose a norm constraint such as $\Vert{x}\Vert \leq 1$.

- One way of satisfying this constraint is to use projected gradient descent, i.e. take the gradient update normally and project it back into the feasible set

- Another way is to rewrite the constrained problem as a modified unconstrained problem. For example, if we want to find the minimum $x$ for some $f(x)$ such that $x$ has unit norm, we could rewrite this as $\min_{\theta} f(\cos\theta, \sin\theta)$ and return $\cos \theta$ an $\sin \theta$ as our solution.

KKT approach

- KKT approach provides a general framework for writing constrained optimization problems as unconstrained ones.

- First, we describe the feasible set $S$ using equality constraints: $g_i(x) = 0$ for $i = 1 … m$ and $h_{j}(x) \leq 0$ for $i = 1 … n$.

- Next we introduce vars for each ofthe constraints, and write down a Lagrangian: $L(x, \lambda, \alpha) = f(x) + \sum_i \lambda_ig_i(x) + \sum_j h_j(x)$.

- Next, we can solve the unconstrained minimization problem $\min_x \max_\lambda \max_{\alpha, \alpha \geq 0} L(x, \lambda, \alpha)$ and this will have the same objective value and set of optimal points to our original constrained optimization problem.

- When the constraints are not satisfied, we can set values for $\lambda_i$ or $\alpha_j$ such that the lagrangian is infinity. This means that no infeasible point can be optimal.

- On the other hand, when the constraints are satisfied, we can show that $\max_{\lambda} max_{\alpha, \alpha \geq 0} L(x, \lambda, \alpha) = f(x)$. This is because when the constraints are satisfied, then the second term will vanish, and the optimal setting give our constraints for the third term is to have $\alpha_j h_j(x) = 0 \forall j$.

- if a constraint is not active, then the solution found woud remaina solution of that constraint was removed. An inactive $h^{i}$ forces all $\alpha$ to be 0.

- To check for optimal points, we can apply the KKT conditions. Note that these conditons are necessary but not sufficient, meaning that if we know that a point satisfies these properties, we can’t immediately say that it is optimal.

- The gradient of the generalized Lagrangian is 0

- All constraints on both $x$ and the inequallity/equality constraints are satisfied

- $\forall \alpha_i h_i(x), \alpha_i h_i(x) = 0$. This is called “complementary slackness”.